The word “preimage” refers to the input of a cryptographic hash function, like SHA256. For instance, the SHA256 hash of the string “foo” is:

1 | 2c26b46b68ffc68ff99b453c1d30413413422d706483bfa0f98a5e886266e7ae |

The byte array 2c26b46... is the hash and the string “foo” is the preimage.

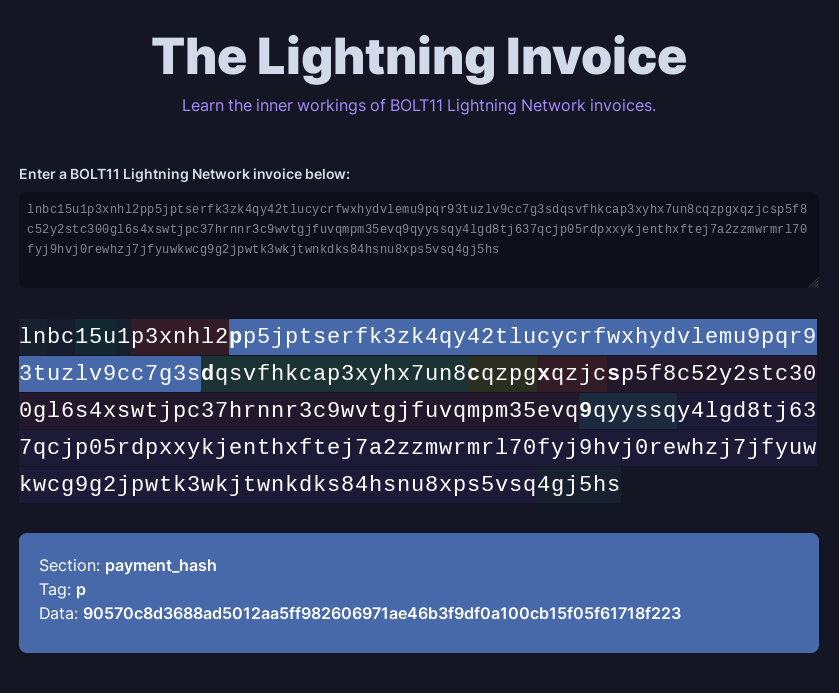

The Bitcoin Lightning Network is, in a functional sense, a really big and complex marketplace for buying SHA256 preimages. Under the hood, when a Lightning Network invoice is generated, the payee samples a random preimage, and then runs that preimage through SHA256 to produce a payment hash. This payment hash is embedded into the final Lightning Network invoice (alongside other important data fields). When the buyer parses the LN invoice, they see the payment hash.

A Lightning invoice is effectively an offer which claims:

If you can pay me this many satoshis, I will reveal the preimage of this payment hash.

The really useful feature of the lightning network is that the receiver cannot claim the payment without also revealing the preimage - the payment is atomic, thanks to the use of Hash Time Lock Contracts (HTLCs).

You can build lots of cool stuff on top of this, but ultimately hash-locks are limited. Knowing a preimage of some hash isn’t intrinsically useful unless you also know that preimage has some other properties. Sometimes we can engineer those properties:

- Atomic swaps use a common preimage to unlock coins or tokens on a different blockchain.

- Lightning-based invoicing systems use lightning preimages as proof-of-payment.

- The Lightning network incentivizes trustless routed payments by giving each node in the route a way to earn fees for routing payments, once they learn a given preimage.

However, these properties are often limited in scope because the preimage can only ever be provably linked with a single function: the SHA256 hash function.

But if we permit ourselves to use zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs), we can engineer almost any property we want by proving arbitrary statements about the preimage itself. This idea is called Zero Knowledge Contingent Payments (ZKCP), which was originally proposed by Greg Maxwell in 2011.

Enter the ZKP

A zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) system can prove and verify arbitrary computational claims about secret data without necessarily revealing the secret data itself. A common use for ZKPs is proving knowledge of a preimage to a given hash without revealing the preimage, for example.

This is a novel ability, because proving properties of a preimage - even proving that a preimage exists in the first place - usually necessitates revealing that preimage. In the context of the Lightning Network, that would obviously not be possible, because the receiver can’t reveal the preimage until the sender offers a payment. Similarly, the sender won’t want to offer payment until they’re sure that the preimage they’re buying actually has the property they desire. ZKPs can bridge this gap.

Zero-Knowledge Proof Systems

Zero-knowledge proof systems can generally be grouped into two categories: STARKs and SNARKs.

- STARK: “Zero-Knowledge Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge”

- SNARK: “Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-interactive Argument of Knowledge”

| Properties | ZK-STARKs | ZK-SNARKs |

|---|---|---|

| Prover Speed | Slow | Slow |

| Verifier Speed | Fast | Instant |

| Proof size | 100s of kilobytes | 100s of bytes |

| Quantum Resistant | Yes | No |

| Trusted Setup * | No | Yes |

Most SNARKs require a “trusted setup ceremony”, where one or more parties generate some public and private parameters needed to make the whole scheme work. They are then expected to publish the public parameters, and securely erase the private parameters, often called the “toxic waste”. As long as at least one of the trusted parties does securely dispose of their toxic waste (private parameters) then the SNARK proofs generated with the corresponding set of public parameters should be both sound and zero-knowledge.

You might think that the trusted setup ceremony could be done between a prover and verifier using multi-party computation, but this paper claims this is not practical to do securely (it would take hours). This disqualifies trusted-setup zk-SNARKs from applicability to a trustless environment like Bitcoin.

ZK-STARKs do not have this requirement at all though: A STARK proof is fully transparent, requiring no trusted setup beyond agreement on the computation to be proven. As a bonus, they’re also post-quantum-secure! On the down-side, STARK proofs are usually 10s or 100s of kilobytes large, compared to only a few hundred bytes for most SNARKs. Thankfully, these STARKs would not end up on-chain, and so their size is likely of minimal consequence for most ZKCP applications.

As a result, we’ll assume STARKs are used for the rest of this article, as they remove the potential dangers and headaches of SNARKs’ trusted setup. There are some SNARK systems which have transparent setup - those could be used just as well, in place of STARKs.

ZKP Abstraction

In this article, I’m going to treat all ZKP systems as black boxes, without caring about their inner workings. If you want to know how zero-knowledge proofs work internally, break out your Google-Fu and dive down that rabbit hole - It goes pretty deep.

Instead, I just care about the practical effect of a ZKP system used with Bitcoin Lightning, so I’m going to flatten all the STARK systems (of which there are many) down to a generic set of two algorithms: Prove, and Verify.

Prove

The Prove algorithm takes in:

- a program

- secret input/output data

- public input/output data

…and outputs a zero-knowledge proof object

Note how

Verify

The Verify algorithm takes in:

- a program

- a zero-knowledge proof

- public input/output data

…and outputs true if

The secret data

Example

Let’s see a concrete example of how a zero-knowledge proof could be used to make a lightning preimage more valuable.

Alice (the seller) wants to sell a Bitcoin private key

The hash of this private key is

The correct corresponding public key is

Alice gives Bob a lightning invoice with the payment hash

But Bob should be skeptical. How does Bob know that the preimage of the hash

So Alice and Bob construct a program

1 | G = secp256k1_curve_base_point() |

The public output of

Alice can compute a proof

Bob can run

In theory this works. There’s just one small problem: Running secp256k1 point multiplication (K = k * G) inside a zero-knowledge proof compiler is very slow. I tested this exact approach with the RISC0 STARK proof system, and it took 47 minutes to prove the computation.

Optimizing

Thankfully we have an easy optimization available: Schnorr signatures are already a valid zero-knowledge proof of knowledge for a secret key

As a quick refresher, a Schnorr signature

sounds like point multiplication with extra steps. why is this any better?

Because constructing a Schnorr signature inside a zero-knowledge proof compiler can be done with simple integer arithmetic - No secp256k1 point multiplication required.

To make our earlier

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| Secret | ||

| Public |

1 | n = 0xfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffebaaedce6af48a03bbfd25e8cd0364141 # Curve order |

To compute a proof, Alice first samples a random nonce

Next Alice computes

Alice packages together the Schnorr signature

Bob can recompute the Schnorr challenge

Click here for an explanation of why this proves knowledge of

If the Schnorr signature is valid, Bob runs

This approach radically reduces our performance overhead. Instead of 47 minutes, this proof takes only about 20 seconds on my machine, and this could likely be optimized further with lower-level proof systems.

Pseudo-PTLCs

The above example (proving a preimage is also the secret key for a given public key) is of particular interest for Bitcoin Lightning users.

There is an upgrade to Lightning called Point Time Lock Contracts which improves Lightning scaling & routing privacy, while also enabling more complex scriptless smart contracts. The basic premise of a PTLC is similar to that of an HTLC, except instead of the receiver divulging a hash preimage in exchange for payment, they must divulge a certain secret key - more specifically, a signature adaptor secret. See the original PTLC proposal here for more info.

Besides improving the scaling & privacy of LN payments, PTLCs enable all kinds of power features and advancements in protocols adjacent and above the Lightning Network. For instance, PTLCs allow users to verifiably purchase:

- signatures on Bitcoin transactions

- signatures on altcoin transactions (if they also use the secp256k1 curve)

- attestations from a Discreet Log Contract oracle

- shares of a multisignature wallet

- tickets for entry in an off-chain Discreet Log Contract

- statechain transaction signatures

sounds great! how do I use them?

You don’t. At least, not yet.

PTLCs are impossible until the Lightning network has more widespread support for taproot channels. If you’re running a recent version of LND for example, you can manually enable taproot channels by putting this into your lnd.conf file:

1 | [Protocol] |

…and when opening channels, you can pass --channel_type taproot to open a taproot channel, if your peer supports it.

But even then, there is no BOLT specification document yet for PTLC routing, let alone an implementation. For now, PTLCs are a hypothetical pipe-dream of higher-level protocol engineers (leeches) like myself, who like to build things on top of lightning. One day, we’ll have PTLCs, and it will be awesome. For now, we are stuck with preimages as our only viable payment proofs.

The zero-knowledge proof example I gave earlier allows LN users to bridge the gap without waiting on the slow grind of the LN protocol development cycle, and without the need for intermediate nodes in the Lightning Network to upgrade.

No, we don’t gain the privacy and scaling benefits of full-blown PTLCs on LN. But if a preimage salesman has enough time, computational resources, and incentive to generate a zero-knowledge proof that his preimage is also a specific secret key, then the buyer and seller gain enormous flexibility, inherited by the capacity to purchase arbitrary discrete logarithms (secret keys) from each other.

I’m Long on NP

Besides the specific case of proving a preimage is a secret key, a preimage salesman could also prove other arbitrary properties of their preimage. In fact, I’ll show you how a buyer can verifiably purchase a solution to any NP-complete problem, using only the Lightning HTLCs we have today, and the principles used in the earlier example.

For instance, we could prove an LN preimage would reveal:

- a solution to a rubiks cube

- a solution to a sudoku puzzle

- a valid TLS certificate

- the prime factors of a large composite number

- a preimage for a completely different hash function

- the nonce (proof of work) needed to mine a bitcoin block

- a neural network trained on a given set of data

- a schedule satisfying a set of availability constraints

- an efficient travel route to reach a destination within a certain time or distance

- an optimal set of expenses to best utilize a given budget

- a genome which shares certain common DNA sequences with another

To clarify, zero-knowledge proofs won’t solve any of these problems for us - They’ll merely allow us to verifiably purchase a solution, which someone must find first. Once we have a solution, we can use zero knowledge proofs to assert the solution is valid and that the LN preimage would reveal it.

Here’s how the seller sets up the proof.

- Find a

solutionto the buyer’s desired NP-Complete problem. - Sample a random 32-byte encryption key

. - Encrypt the

solutionusing, such that is a viable decryption key. - Create a zero-knowledge proof that the secret

satisfies the following program (pseudocode).

1 | # Test if a solution to our NP-complete problem is valid. |

is the only secret input. - the

encrypted_solutionis a public input. - the hash

is a public output.

The LN seller proves execution of np_problem_test_solution function. If the LN buyer is given the encrypted_solution, then they have an incentive to learn the preimage

One can also prove encryption instead of decryption, asserting instead that a public output ciphertext was generated by symmetrically encrypting a secret input solution using the preimage as key. This must imply that the ciphertext can also be decrypted with the preimage. We’re free to select whichever approach is more efficient for our encryption algorithm.

why does this work for any NP-complete problem?

NP-Complete problems are those for which we have efficient ways to check solutions, but no efficient deterministic option for finding a solution. Since checking a solution is fast, we should be able to build fast-ish zero-knowledge proofs to assert a solution is valid without exposing the solution. We would run the actual search computation outside of the zero-knowledge proof system, and then use a ZKP to prove the solution is correct (and related to the LN preimage).

This is always possible because any NP-statement can be proven in zero knowledge.

why not use the solution as the preimage? why bother encrypting it?

That can be done in some cases, but it may not be safe. Lightning preimages must always be exactly 32-bytes long. If our search space of possible solutions is at most size

If the entropy of the solution is too low, or if the np_problem_test_solution function is faster than running sha256, then an intermediary LN routing node could use these advantages to speed up a search for the preimage

The easiest way to get around this is for the seller to give some kind of shared state to the buyer, which is needed to fully transform the preimage solution. This prevents intermediary LN routing nodes from gaining any advantage in guessing encrypted_solution, but one could do it in other more efficient ways too, depending on the use-case.

Modularity

Everything we’ve discussed above applies not only to Bitcoin Lightning, but also to any other payment protocol which has a cryptographically verifiable proof-of-payment similar to LN.

For instance, the buyer and seller could create an on-chain PTLC, bypassing the need for native Lightning PTLC support, and the seller can prove the adaptor signature secret has arbitrary properties. For some ZKP systems, this might be significantly more efficient because (as demonstrated earlier) discrete logs can be proven in zero knowledge compilers very efficiently using simple integer arithmetic, whereas SHA256 proofs are often hard for ZKP compilers to optimize.

I focused on the Lightning Network in particular because LN is probably the largest, most mature, most liquid, and most agile marketplace for secrets (SHA256 preimages) in the world today, with all the APIs already in-place needed to practically authenticate and then sell arbitrary secrets.

LND‘s command line interface, lncli and the LND REST API both support arbitrary preimages when creating invoices. For example, this command creates a BOLT11 invoice with a custom preimage, using the big-endian representation of the number 4.

1 | lncli addinvoice 1000 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000004 |

When paying an LN invoice, most LN clients and APIs will give the buyer access to the preimage as a form of receipt to prove they completed the payment. This accessibility and flexibility around preimages makes it easy to build a zero-knowledge application which uses those preimages, on top of Lightning.

Trade Offs

ZKPs come with drawbacks. Proving and verifying in zero-knowledge is a very mathematically complex process, regardless of which protocol is used. The code needed to implement them in the real-world is usually very big, slow, and involves many moving parts which can present large attack surfaces.

In more pragmatic terms:

- The

algorithm often takes seconds, minutes, or even hours, depending on the runtime complexity of the being proven. - The

algorithm is sensitive to implementation faults, which might lead it to accept false proofs. - In the case of STARKs, the proof

is often very large. A relatively simple STARK proving knowledge of a SHA256 preimage is 100+ kilobytes when serialized. Adding further constraints on the preimage would increase the proof size even more.

It wouldn’t be practical for LN receivers to generate zero-knowledge proofs for every single payment request, as that would open them up to denial-of-service attacks. Most lightning micropayments just don’t need this kind of firepower to back the seller’s claim: I don’t care if the 100 sats I pay for a ChatGPT conversation will actually answer my NP-complete question about seating arrangements at a wedding.

However, if I’m paying for something much more valuable, then perhaps the extra compute overhead would be worthwhile for the seller to convince me. Perhaps if I’m buying something expensive like a genome, or a ransomware decryption key, or an advanced neural network, I’d like to be a little more certain that my purchase is going to be genuine, especially if the seller I’m buying from lacks credibility.

And of course, for this to be at all practical, searching for a solution must take significantly more time than it would take to compute a zero-knowledge proof that an existing solution is valid - otherwise why would the buyer not simply compute a solution himself?

Soundness

ZKPs have a high cognitive overhead. That’s fancy-speak for “they’re hard to understand”.

Because of their technical complexity, it is not easy to audit open source ZKP implementations for flaws, nor to write secure implementations from scratch. This means would-be ZKP users have few safe options.

The READMEs of most zero-knowledge proof implementation available today are plastered with various warnings disclaiming their suitability for real-world use.

- “DO NOT USE IN PRODUCTION” -distaff

- “has not yet undergone extensive review or testing” -libsnark

- “has not been reviewed or audited. It is not suitable to be used in production” -Noir Lang

- “has not been audited and may contain bugs and security flaws” -Miden VM

- “still under construction … don’t recommend using it in production” -Triton VM

- “has not been thoroughly audited and should not be used in production” -o1-labs/snarky

- “should not be used in any production systems” -0xPolygonZero/plonky2

- “unstable and still needs to undergo an exhaustive security analysis” -dusk-network/plonk

- “contains multiple serious security flaws, and should not be relied upon” -libSTARK (a STARK library written by the inventor of ZK-STARKs)

Ironically, many ZKP systems are being used in production systems, usually altcoins.

With this fragility in mind, a buyer may ask the seller for multiple proofs from distinct ZKP implementations, and reject the claim if any proofs fail to validate.

Intuitively, if the seller’s claim is true, she should be able to create valid proofs using any general ZKP system. This improves the buyer’s confidence that the seller’s claim about the preimage is sound. Even if every ZKP implementation they use is flawed, the chance of the seller knowing those zero days for all of them is very small.

Assume any given ZKP system/implementation has a probability

Say we use

This makes practical attacks against the buyer exponentially harder, at the expense of a linear increase in proof-generating time for the seller.

The buyer could also randomly select one or more proof systems from a set of candidate systems, and then demand the seller prove properties of the preimage using his chosen systems. This could improve performance, because the seller doesn’t necessarily need to build proofs under every candidate ZKP system - Just a subset selected by the buyer.

Conclusion

I’m unsure to what extent this approach is practically useful today, largely due to the slow proving time of most ZKP systems, but the optionality it provides is enormously significant. Perhaps this could fill a niche in commerce which deals with the exchange of valuable secret data, such as in the zero-day market, or in the world of AI, where purchasing secrets is normally a difficult thing to do safely. It can also be used as a bridge, connecting protocols which were previously incompatible.

Avoiding ZKPs is the best general advice for Bitcoin protocol design, because ZKPs introduce more problems than they solve in most cases. But Bitcoiners should keep this idea in their pocket though, and be aware of the new possibilities we see when we widen our perspective.

Resources

For those interested in exploring real-world ZKP systems, I’ve appended a list of some projects and resources below.

STARK Systems

- https://github.com/facebook/winterfell

- https://github.com/TritonVM/triton-vm

- https://github.com/risc0/risc0

- https://github.com/GuildOfWeavers/distaff

- https://github.com/0xPolygonMiden/miden-vm

- https://github.com/valida-xyz/valida

- https://github.com/starkware-libs/cairo-lang

- https://github.com/andrewmilson/ministark

SNARK systems

- https://github.com/ConsenSys/gnark

- https://github.com/arkworks-rs

- https://github.com/scipr-lab/libsnark

- https://github.com/zkcrypto/bellman

- https://github.com/Zokrates/ZoKrates

- https://github.com/microsoft/Spartan

- https://zkwasmdoc.gitbook.io/

- https://github.com/ProvableHQ/leo

- Circom ecosystem

ZKCP Background

- https://bitcoincore.org/en/2016/02/26/zero-knowledge-contingent-payments-announcement/

- https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=357263.0

- https://bitcoinops.org/en/topics/acc/

- https://freedom-to-tinker.com/2017/06/08/breaking-fixing-and-extending-zero-knowledge-contingent-payments/

- https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3319535.3354234